Our Health Library information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Please be advised that this information is made available to assist our patients to learn more about their health. Our providers may not see and/or treat all topics found herein.

Cervical Cancer Screening: Screening - Patient Information [NCI]

This information is produced and provided by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The information in this topic may have changed since it was written. For the most current information, contact the National Cancer Institute via the Internet web site at http://cancer.gov or call 1-800-4-CANCER.

Cervical Cancer Screening

Screening means checking for a disease before there are symptoms. Cervical cancer screening is an important part of routine health care for people who have a cervix.

What is cervical cancer screening?

The goal of screening for cervical cancer is to find precancerous cervical cell changes, when treatment can prevent cervical cancer from developing. Sometimes, cancer is found during cervical screening. Cervical cancer found at an early stage is usually easier to treat. By the time symptoms appear, cervical cancer may have begun to spread, making treatment more difficult.

There are three main ways to screen for cervical cancer:

- The human papillomavirus (HPV) test checks cells for infection with high-risk HPV types that can cause cervical cancer.

- The Pap test (also called a Pap smear or cervical cytology) collects cervical cells so they can be checked for changes caused by HPV that may—if left untreated—turn into cervical cancer. It can find precancerous cells and cervical cancer cells. A Pap test also sometimes finds conditions that are not cancer, such as infection or inflammation.

- The HPV/Pap cotest uses an HPV test and Pap test together to check for both high-risk HPV and cervical cell changes.

When to get screened for cervical cancer

Cervical screening recommendations are developed by several organizations, including the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the American Cancer Society (ACS). How often you should be screened for cervical cancer and which tests you should get will depend on your age and health history. Because HPV vaccination does not prevent infection with all high-risk HPV types, vaccinated people who have a cervix should follow cervical cancer screening recommendations.

Age 21-29 years

If you are in this age group, USPSTF recommends getting your first Pap test at age 21, followed by Pap testing every 3 years. Even if you are sexually active, you do not need a Pap test before age 21.

Age 30-65 years

If you are in this age group, USPSTF recommends getting screened for cervical cancer using one of the following methods:

- HPV test every 5 years

- HPV/Pap cotest every 5 years

- Pap test every 3 years

Updated cervical cancer screening guidelines from ACS recommend starting screening at age 25 with an HPV test and having HPV testing every 5 years through age 65. However, testing with an HPV/Pap cotest every 5 years or with a Pap test every 3 years is still acceptable. To read about the reasons for updates to the guidelines, visit ACS's Updated Cervical Cancer Screening Guidelines Explained.

Older than 65 years

If you are in this age group, talk with your health care provider to learn if screening is still needed. If you have been screened regularly and had normal test results, your health care provider will probably advise you that you no longer need screening. However, if your recent test results were abnormal or you have not been screened regularly, you may need to continue screening beyond age 65.

Exceptions to the cervical cancer screening guidelines

Your health care provider may recommend more frequent screening if:

- you are HIV positive

- you have a weakened immune system

- you were exposed before birth to a medicine called diethylstilbestrol (DES), which was prescribed to some pregnant women through the mid 1970s

- you had a recent abnormal cervical screening test or biopsy result

- you have had cervical cancer

If you've had an operation to remove both the uterus and cervix (called a total hysterectomy) for reasons not related to cancer or abnormal cervical cells you do not need to be screened for cervical cancer. However, if your hysterectomy was related to cervical cancer or precancer, talk with your health care provider to learn what follow-up care you need. If you've had an operation to remove the uterus but not the cervix (sometimes called a partial or supracervical hysterectomy) you should continue routine cervical cancer screening.

Where to get screened for cervical cancer

Doctors' offices, clinics, and community health centers offer HPV and Pap tests. Many people receive these tests from their ob/gyn (obstetrics/gynecology) or primary care provider.

If you don't have a primary care provider or doctor you see regularly, you can find a clinic near you that offers cervical cancer screening by contacting:

- your state or local health department

- the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP) or call 1-800-232-4636; NBCCEDP provides low-income, uninsured, and underserved people access to timely cervical cancer screening and diagnostic services

- a Planned Parenthood clinic, or call 1-800-230-7526

- NCI's Cancer Information Service, or call 1-800-422-6237

Cervical screening test results usually come back from the lab in about 1–3 weeks. If you don't hear from your health care provider, call and ask for your test results. Make sure you understand any follow-up visits or tests you may need.

What to expect during a cervical cancer screening test

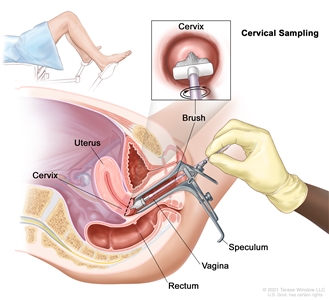

Cervical cancer screening tests are usually done during a pelvic exam, which takes only a few minutes. During the exam, you lie on your back on an exam table, bend your knees, and put your feet into supports at the end of the table. The health care provider uses a speculum to gently open your vagina to see the cervix. A soft, narrow brush or tiny spatula is used to collect a small sample of cells from your cervix. You may have the option to self-collect the cervical sample during your appointment. If you're interested in this option, talk with your health care provider to learn more.

Cervical sampling. A speculum is inserted into the vagina to widen it. Then, a brush is inserted into the vagina to collect cells from the cervix.

The sample is then sent to a lab, where the cells can be checked to see if they are infected with the types of HPV that cause cancer (an HPV test). The same sample can be checked for abnormal cells (a Pap test). When both an HPV test and a Pap test are done on the same sample, this is called an HPV/Pap cotest.

A pelvic exam may include more than taking samples for an HPV and/or Pap test. Your health care provider may also check the size, shape, and position of the uterus and ovaries and feel for any lumps or cysts. The rectum may also be checked for lumps or abnormal areas. You may talk with your health care provider about being tested for sexually transmitted infections.

Most health care providers will tell you what to expect at each step of the exam, so you will be at ease.

Researchers have found that cervical cancer screening may be less effective for people with obesity, possibly because of challenges in visualizing the cervix and obtaining a cell sample. Approaches to improve cervical visualization, including the use of larger speculum, may be helpful.

Does cervical cancer screening have any risks?

Cervical cancer screening saves lives. Very few people screened for cervical cancer at routine intervals develop cervical cancer. Screening can detect cervical changes early, lowering a person's chance of dying from cervical cancer. Despite these benefits, cervical screening is not perfect, and there are several possible harms to be aware of. Before having any screening test, you may want to discuss the test with your doctor.

Potential risks of harm from cervical cancer screening include:

- Unnecessary follow-up tests and treatment: Finding a condition through screening that would not have caused problems may lead to unnecessary follow-up tests and possibly treatment. The current recommended screening intervals and tests reduce the chance of finding and treating cervical cell abnormalities that would have gone away on their own.

- False-positive test results: Screening test results may sometimes appear abnormal even though no precancer or cancer is present. When a Pap test shows a false-positive result (one that shows there is precancer or cancer when there isn't), it can cause anxiety and is usually followed by more tests and procedures (such as colposcopy, cryotherapy, or loop electrosurgical excision procedure), which also have harms.

- False-negative test results: Screening test results may appear normal even though cervical precancer or cancer is present. A person who receives a false-negative test result (one that shows there is no cancer when there is) may delay seeking medical care even if there are symptoms.

For a downloadable booklet about cervical cancer screening, visit Understanding Cervical Changes: A Health Guide.

HPV and Pap Test Results: Next Steps after an Abnormal Cervical Cancer Screening Test

People who have cervical cancer screening at regular intervals are rarely found to have cancer. Most people who receive abnormal cervical cancer screening results either have human papillomavirus (HPV) infections or have early cell changes that can be monitored (since they often go away on their own) or treated early (to prevent the development of cervical cancer).

See Cervical Cancer Screening for information about when to get screened and what to expect during the tests.

HPV test results: What positive and negative results on a screening test mean

HPV test results show whether high-risk HPV types were found in cervical cells. An HPV test will come back as a negative test result or a positive test result.

- Negative HPV test result: High-risk HPV was not found. You should have the next test in 5 years. You may need to come back sooner if you had abnormal results in the past.

- Positive HPV test result: High-risk HPV was found. Your health care provider will recommend follow-up steps you need to take, based on your specific test result.

What does it mean if you have a positive HPV test after years of negative tests?

Sometimes, after several negative HPV tests, a woman may have a positive HPV test result. This is not necessarily a sign of a new HPV infection. Sometimes an HPV infection can become active again after many years. Some other viruses behave this way. For example, the virus that causes chickenpox can reactivate later in life to cause shingles.

Researchers don't know whether a reactivated HPV infection has the same risk of causing cervical cell changes or cervical cancer as a new HPV infection.

Pap test results: What normal, abnormal, and unsatisfactory screening test results mean

Pap test results show whether cervical cells are normal or abnormal. A Pap test may also come back as unsatisfactory.

Normal Pap test results: No abnormal cervical cells were found. A normal test result may also be called a negative test result or negative for intraepithelial lesion (area of abnormal growth) or malignancy.

Unsatisfactory Pap test results: The lab sample may not have had enough cells, or the cells may have been clumped together or hidden by blood or mucus. Your health care provider will ask you to come in for another Pap test in 2 to 4 months.

Abnormal Pap test results: An abnormal test result may also be called a positive test result. Some of the cells of the cervix look different from the normal cells. An abnormal test result does not mean you have cancer. Your health care provider will recommend monitoring, more testing, or treatment.

Abnormal Pap test results include

- Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US): This is the most common abnormal Pap test finding. It means that some cells don't look completely normal, but it's not clear if the changes are caused by HPV infection. Other things can cause cells to look abnormal, including irritation, some infections (such as a yeast infection), growths (such as polyps in the uterus), and changes in hormones that occur during pregnancy or menopause. Although these things may make cervical cells look abnormal, they are not related to cancer. Your health care provider will usually do an HPV test to see if the changes may be caused by an HPV infection. If the HPV test is negative, estrogen cream may be prescribed to see if the cell changes are caused by low hormone levels. If the HPV test is positive, you may need additional follow-up tests.

- Atypical glandular cells (AGC): Some glandular cells were found that do not look normal. This can be a sign of a more serious problem up inside the uterus, so your health care provider will likely ask you to come back for a colposcopy.

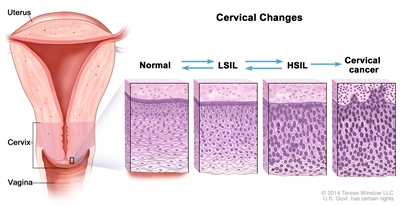

- Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL): There are low-grade changes that are usually caused by an HPV infection. Your health care provider will likely ask you to come back for additional testing to make sure that there are not more serious (high-grade) changes.

- Atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (ASC-H): Some abnormal squamous cells were found that may be a high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL), although it's not certain. Your health care provider will likely ask you to come back for a colposcopy.

- High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL): There are moderately or severely abnormal cervical cells that could become cancer in the future if not treated. Your health care provider will likely ask you to come back for a colposcopy.

- Adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS): An advanced lesion (area of abnormal growth) was found in the glandular tissue of the cervix. AIS lesions may be referred to as precancer and may become cancer (cervical adenocarcinoma) if not treated. Your health care provider will likely ask you to come back for a colposcopy.

- Cervical cancer cells (squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma): Cancer cells were found; this finding is very rare for people who have been screened at regular intervals. If a biopsy shows that cervical cancer is present, your doctor will order certain tests to find out if cancer cells have spread within the cervix or to other parts of the body. See the Cervical Cancer Diagnosis page for information about tests that may be used to diagnose and stage cervical cancer.

Cervical changes. The cervix is the lower, narrow end of the uterus that forms a canal between the uterus and vagina. Before cancer cells form in tissues of the cervix, the cells of the cervix go through abnormal changes called dysplasia. There are different types of dysplasia. Mild dysplasia, called low-grade intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) is one type. Moderate or severe dysplasia, called high-grade intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) is another type of dysplasia. LSIL and HSIL may or may not become cancer.

Follow-up tests and procedures after an abnormal Pap test (Pap smear) or HPV test

Keep in mind that most people with abnormal cervical screening test results do not have cancer. However, if you have an abnormal test result, it's important to get the follow-up care that your health care provider recommends.

Until recently, follow-up recommendations were based on the results of a person's most recent cervical screening test. However, updated ASCCP risk-based management consensus guidelines advise a more tailored approach to follow-up care.

What these updated guidelines mean is that, in addition to your current Pap, HPV, or cotest screening result, your health care provider will consider additional factors when recommending follow-up care, including

- previous screening test results

- previous treatments for precancerous cervical cell changes

- personal health factors, such as your age

Based on your individual risk of developing severe cervical cell changes that could become cervical cancer, you may be advised to

- return for a repeat HPV test or HPV/Pap cotest in 1 or 3 years

- have a colposcopy and biopsy

- receive treatment; see Treatment for high-grade cervical cell changes

These updated guidelines focus on detecting and treating severe cervical cell changes that could develop into cervical cancer while also decreasing testing and treatment for less severe conditions (low-grade cervical cell changes).

Colposcopy

During a colposcopy, your doctor inserts a speculum to gently open the vagina and see the cervix. A vinegar solution is applied to the cervix to help show abnormal areas. Your doctor then places an instrument called a colposcope close to the vagina. It has a bright light and a magnifying lens and allows your doctor to look closely at your vagina and cervix for abnormal areas.

A colposcopy usually includes a biopsy, so that the cells or tissues can be checked under a microscope for signs of disease, including cervical cancer.

Cervical biopsy

A biopsy is a procedure used to remove cervical cells or tissue to be checked under a microscope for abnormal cervical cells, including cancer. In addition to removing a sample for further testing, some types of biopsies may be used as treatment, to remove abnormal cervical tissue or lesions.

Talk with your doctor to learn what to expect during and after your biopsy procedure. Bleeding and/or discharge after a biopsy may occur. Some people have pain that feels like cramps during menstruation.

Biopsy findings: cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN)

Biopsy samples are checked by a pathologist for CIN. CIN is the term used to describe abnormal cervical cells that were found on the surface of the cervix after a biopsy.

CIN is graded on a scale of 1 to 3, based on how abnormal the cells look under a microscope and how much of the cervical tissue is affected. LSIL changes seen on a Pap test are generally CIN 1. HSIL changes seen on a Pap test can be CIN 2, CIN2/3, or CIN 3.

- CIN 1 changes are mild, or low grade. They usually go away on their own and do not require treatment.

- CIN 2 changes are moderate and are typically treated by removing the abnormal cells. However, CIN 2 can sometimes go away on its own. Some people, after consulting with their health care provider, may decide to have a colposcopy with biopsy every 6 months. CIN 2 must be treated if it progresses to CIN 3 or does not go away in 1 to 2 years.

- CIN 3 changes are severely abnormal. Although CIN 3 is not cancer, it may become cancer and spread to nearby normal tissue if not treated. Doctors do not yet have a way to tell which cases of CIN 3 will become cancer and which will not. CIN 3 should be treated right away, unless you are pregnant. See Pregnancy and Treatment for High-Grade Cervical Cell Changes for more information.

Treatment for high-grade cervical cell changes

The goal of treating high-grade cervical cell changes is to remove or destroy abnormal cervical cells that have a high chance of becoming cancer. Some of these treatments are also used for early-stage cervical cancer.

The most common treatment for high-grade cervical cell changes is conization, the removal of a cone-shaped piece of tissue from the cervix and cervical canal. There are two types of conization.

- Loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) uses a thin wire loop, through which an electrical current is passed, to remove abnormal tissue. This procedure is typically done in a doctor's office. It usually takes only a few minutes, and local anesthesia is used to numb the area.

- Cold knife conization uses a scalpel to remove the abnormal tissue. This procedure is done at the hospital under general anesthesia.

Several other treatments may also be used.

- Laser therapy uses a laser (narrow beam of intense light) to remove or destroy abnormal tissue. This is an outpatient procedure that may be done under local or general anesthesia.

- Cryotherapy uses a special cold probe to destroy abnormal tissue by freezing it. This procedure is done at a doctor's office. It takes only a few minutes and usually does not require anesthesia.

- Total hysterectomy is the surgical removal of the uterus and cervix. It is often used to treat AIS. It is used to treat CIN3 only if the abnormal cells were not completely removed by other treatments.

Pregnancy and treatment for high-grade cervical cell changes

Rarely, procedures to treat cervical cell abnormalities can weaken the cervix, increasing the risk of premature birth or miscarriage.

If you are pregnant or plan to become pregnant, your health care provider will talk with you about procedures that are recommended for you and the timing of these procedures. Depending on your specific diagnosis, you may be treated postpartum, or after delivery.

For a downloadable booklet about cervical cancer screening, see Understanding Cervical Changes: A Health Guide.

Last Revised: 2025-02-13

If you want to know more about cancer and how it is treated, or if you wish to know about clinical trials for your type of cancer, you can call the NCI's Cancer Information Service at 1-800-422-6237, toll free. A trained information specialist can talk with you and answer your questions.

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Ignite Healthwise, LLC disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. Learn how we develop our content.

Healthwise, Healthwise for every health decision, and the Healthwise logo are trademarks of Ignite Healthwise, LLC.